Christiana Figueres, who negotiated the Paris Climate Accord, discusses creating a global obligation to protect the seas. (video provided by the BBC)

Should we put an end to the open ocean?

Currently, more than 60 percent of the ocean carries no rules because it lies beyond national jurisdiction, according to a United Nations report. This means that the majority of the seas belong to no nation because it lies too far out from land.

This may sound like a good thing if you want a hassle-free ocean. But it’s not.

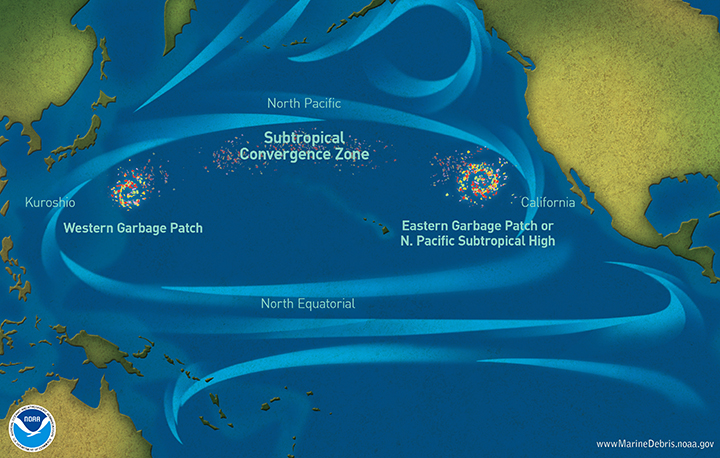

A map of large islands of trash floating around the North Pacific ocean. Image courtesy of NOAA.

The fact that most of the ocean remains in legal limbo — with no binding law of the land to protect it — has left the sea open to rampant abuse. Pollution, overfishing, deep sea mining — none of these carry real consequence because the high seas don’t belong to a specific nation. It’s not anyone’s backyard, so to speak.

A Paris Climate Accord for the high seas?

However, due to the success of the Paris Climate Accord, there is a new push to regulate that remaining 60 percent on the international level.

Christiana Figueres, the chief negotiator for the Paris Climate Accord in 2016, calls the high seas part of the “global commons” — a term attached to territories “that belong to everyone and no one.”

Being part of the global commons doesn’t guarantee international protection, but it doesn’t prohibit it, either.

The authors of the UN report — which was circulated last month during the Ocean Conference in New York — filed it to inform international delegates of the threats posed by continued abuse. The UN is currently drafting a resolution on the governance of the ocean.

This resolution comes just in time as countries and corporations around the world turn toward the ocean for fossil fuels and other materials.

A rising demand for resources, coupled with insufficient environmental policy, threatens to further exacerbate areas of the ocean currently in crisis.

Parts of the ocean face complete collapse

Boats carry statues of the Hindu god Ganesh to throw out to the Bay of Bengal. 400 million people live around the Bay, which may see the complete collapse of its ecosystems. Photograph by Jacques de Lannoy for The Guardian.

One such area is the Bay of Bengal, which saw massive algae blooms and the creation of dead zones due to agricultural run-off.

“You have to remember there are 400 million people living [a]round the rim of the bay,” Dr. Greg Cowie from the University of Edinburgh, one of the report’s authors, told the BBC. “There are half a million fishers. If the situation gets much worse we are going to get a huge human problem.”

To illustrate how dependent humans are on the ocean’s resources: 38 percent of the world’s population lives within sixty-three miles of the shoreline, and 67 percent live within two hundred fifty miles, according to the United Nations World Oceans Assessment.